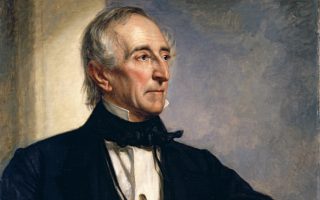

lettersforvivian.org – William Howard Taft, the 27th President of the United States, is often remembered for his struggle to balance the competing forces of conservatism and progressivism during his presidency. His time in office (1909-1913) saw a political divide that reflected a broader national debate about the role of government in regulating business, protecting workers, and promoting social welfare. Although Taft was initially seen as the natural successor to his former mentor, Theodore Roosevelt, his more cautious and legalistic approach to reform put him at odds with the very Progressive movement that had swept Roosevelt into power.

Taft’s presidency was shaped by a series of policy decisions, both domestic and foreign, that led to a growing rift between him and the Progressives. His attempts to navigate the political pressures from both conservatives and progressives marked his time in office as one of increasing tension and division. Ultimately, his presidency would become a key chapter in the Progressive Era, as it illuminated the complexities and internal contradictions within the movement itself.

This article explores the major struggles Taft faced in dealing with the Progressive movement, highlighting the key issues that divided him from progressives, the policies he implemented, and the consequences of his inability to fully align with this transformative political movement.

The Context of the Progressive Movement

The Rise of Progressivism

The Progressive Era, which spanned from the 1890s to the 1920s, was a period of social, political, and economic reform in the United States. Progressives sought to address the challenges posed by industrialization, urbanization, and corruption in both government and business. They advocated for government intervention to regulate monopolies, improve working conditions, protect consumers, and extend civil rights. The movement was fueled by a belief that the federal government could and should play an active role in correcting social and economic inequalities.

Key figures in the Progressive movement included journalists, activists, and reform-minded politicians who called for changes such as antitrust laws, labor rights, women’s suffrage, and greater accountability for political leaders. Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th President, became the face of the Progressive movement with his “Square Deal” policies that emphasized fairness, conservation, and regulation of big business.

Taft’s Early Relationship with Progressivism

When Taft succeeded Roosevelt as president in 1909, he initially seemed like a natural continuation of Roosevelt’s progressive reforms. Taft had been Roosevelt’s trusted ally and was often seen as his heir apparent. Roosevelt had supported Taft’s candidacy, believing that he would carry forward his policies. However, Taft’s background as a lawyer, judge, and legal thinker shaped his more restrained approach to reform, and as his presidency unfolded, it became clear that he had a fundamentally different approach to progressivism than Roosevelt.

While Roosevelt had used the presidency as a platform for bold action, using his personal influence to push progressive reforms, Taft preferred a more legalistic and constitutional approach to policy. This divergence in their approaches ultimately caused significant friction between Taft and the Progressive movement.

Key Struggles with Progressivism

The Tariff Debate: A Defining Issue

One of the most significant points of contention between Taft and progressives was his handling of tariff reform. Tariffs—taxes on imported goods—had long been a contentious issue in American politics. While progressives wanted to lower tariffs to reduce the cost of goods for consumers, conservative Republicans argued that high tariffs were necessary to protect American industries from foreign competition.

Taft campaigned for lower tariffs in the 1908 election, promising to reduce tariff rates that had been set by the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909. However, once in office, Taft was faced with significant opposition from protectionist Republicans, who were resistant to tariff reductions. The result was the passage of the Payne-Aldrich Tariff, which was a compromise bill that only modestly reduced tariffs and, in some cases, raised them. This bill angered progressives, who felt that Taft had betrayed his campaign promises and sided with conservative interests.

The tariff issue was emblematic of the larger tensions within the Republican Party and the Progressive movement. Progressives viewed Taft’s support for the Payne-Aldrich Tariff as a sign that he was more concerned with maintaining party unity and appeasing conservative Republicans than with pursuing genuine reform. This marked the beginning of a broader rift between Taft and the Progressive wing of his party, and it alienated many of Roosevelt’s former supporters.

The Ballinger-Pinchot Affair: Conservation at the Crossroads

Another issue that significantly strained Taft’s relationship with progressives was his handling of conservation, a cause championed by Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt had been a strong advocate for preserving America’s natural resources, and during his presidency, he expanded the National Parks system and created the U.S. Forest Service. Roosevelt believed that conservation was a matter of national importance, and he used his presidential power to protect public lands from exploitation.

However, Taft’s approach to conservation was more cautious and less aggressive. In 1910, a controversy known as the Ballinger-Pinchot Affair erupted, which would have a lasting impact on Taft’s standing with progressives. Richard Ballinger, Taft’s Secretary of the Interior, was accused by Gifford Pinchot, the head of the U.S. Forest Service, of opening up public lands in Alaska to private development, including coal mining. Pinchot, a staunch conservationist and Roosevelt ally, publicly criticized Ballinger, accusing him of corruption and mismanagement.

Taft, in an effort to maintain party unity, defended Ballinger and removed Pinchot from his position. This decision angered progressives, who saw it as a betrayal of Roosevelt’s conservation policies. Pinchot’s dismissal, coupled with Taft’s perceived failure to prioritize conservation, caused a significant rift between Taft and the Progressive movement. Roosevelt, who had once seen Taft as his protégé, became increasingly disillusioned with his successor’s handling of conservation and other issues, setting the stage for a bitter rivalry that would shape the 1912 election.

Trust-Busting: Legalism Over Bold Action

Taft’s approach to trust-busting—breaking up monopolies and regulating large corporations—was another area in which he clashed with progressives. Like Roosevelt, Taft was committed to using the power of the federal government to break up monopolies and regulate big business. However, Taft’s approach to trust-busting was more legalistic and restrained than Roosevelt’s.

While Roosevelt had been known for his use of executive power and his willingness to take bold action against trusts, Taft was more cautious and preferred to use the courts to address antitrust issues. His administration filed over 90 antitrust suits—twice as many as Roosevelt’s—but Taft’s reliance on legal processes meant that the outcomes of these cases were often slow and incremental, rather than the dramatic results that progressives had hoped for.

Taft’s legalistic approach to trust-busting alienated many progressives who were frustrated by the pace of reform. They viewed Taft’s reluctance to use the presidency as a platform for more aggressive action as a failure to meet the demands of the Progressive movement. As a result, Taft’s trust-busting efforts, while legally significant, were seen by many as insufficient in addressing the growing power of monopolies and corporations.

The Republican Split: Roosevelt vs. Taft

As the 1912 election approached, the growing division between Taft and the Progressive wing of the Republican Party became more pronounced. The final straw for many progressives was Taft’s reluctance to pursue comprehensive reform on issues like tariffs, conservation, and labor rights. By 1912, Roosevelt had become openly critical of Taft’s presidency, accusing him of betraying the Progressive cause and abandoning the reforms that Roosevelt had championed.

Roosevelt, emboldened by his legacy and frustrated by Taft’s more conservative approach, decided to challenge Taft for the Republican nomination in 1912. This led to a bitter battle between the two men, with Roosevelt claiming that Taft had “betrayed” the Progressive movement. When Taft secured the Republican nomination, Roosevelt bolted from the party and formed the Progressive (“Bull Moose”) Party, running as a third-party candidate in the 1912 election.

The split between Taft and Roosevelt resulted in a fractured Republican Party, and both men ultimately lost to the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson, who won the presidency in a landslide. The 1912 election marked the culmination of Taft’s struggles with the Progressive movement and the end of the Republican Party’s dominance in national politics for the time being.

The Legacy of Taft’s Struggles with Progressivism

A Complicated Legacy

William Howard Taft’s presidency was marked by a series of struggles with the Progressive movement that left a lasting impact on American politics. While Taft pursued reforms such as trust-busting and tariff reductions, his more cautious and legalistic approach alienated many progressives who had hoped for bolder, more direct action. His handling of conservation issues and the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act also contributed to the erosion of support from the Progressive wing.

Ultimately, Taft’s inability to fully embrace the Progressive movement left him isolated from both conservatives and progressives, resulting in the bitter split within the Republican Party. Despite his legal and administrative achievements, Taft’s presidency is often seen as a missed opportunity to build a lasting Progressive coalition.

However, Taft’s legacy is not solely defined by his struggles with progressivism. His later career as Chief Justice of the United States, where he played a pivotal role in modernizing the federal judiciary, remains a significant and often overlooked part of his legacy. As Chief Justice, Taft’s commitment to law, fairness, and efficiency stood in contrast to the more partisan politics of his presidency, showcasing his deep dedication to the rule of law and constitutional principles.

Conclusion: The Struggle for Balance

William Howard Taft’s presidency was characterized by his attempt to balance the competing demands of the Progressive movement and the conservative forces within his own party. While he shared some of the Progressive goals, his more cautious approach to reform and his reliance on legal processes often put him at odds with progressives who desired more immediate and bold action. His struggle to navigate this divide ultimately led to a political rupture with his former mentor, Theodore Roosevelt, and the fracturing of the Republican Party. Though Taft’s time in office was marked by tension and division, his contributions to American law and governance, both as president and later as Chief Justice, continue to shape the nation’s legal landscape today.